GUEST BLOGGER LISA L. OWENS

Just as no human enters the world walking and talking, no one at any age should expect to become highly skilled at something new without lots of practice. That’s true whether you’re learning to pilot a plane, write poetry, or do almost anything at all.

Women Pilots of World War II (Lerner, 2018) gives young readers a bird’s-eye view of the know-how possessed by the first wave of women to fly planes for the military. These pilots participated in rigorous flight-training programs to learn specialized math, physics, and geography concepts; the mechanics of operating a plane; and effective communication with those involved in each flight’s (and the war’s) mission.

In this discussion, students will explore the nature of World War II pilots’ work and consider the role practice plays in their own evolving skill sets.

Share

Share the summary below and have students read the book. Note: The summary can also be used on its own for those without access to the book.

World War II marked the first time women pilots were trained to fly military planes in the United States. Although most were not allowed to fly combat missions, they provided great service to the Allied forces. Women Pilots of World War II spotlights the brave women in the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union who trained, flew, and fought for the Allies, blazing an exciting new path for women in the military.

Discuss a pilot’s knowledge base and the nature of skills acquisition.

Ask students to brainstorm a list of skills, big and small, that a World War II pilot would have needed. Refer to scenes from the book if necessary.

Have volunteers respond to the following:

- Name one skill from our list that you have.

- Reveal one skill from the list you would like to have. How long do you think it might take to get good at that? What’s the first thing you’d do to get started?

Explain that, except for innate functions like breathing and crying, humans aren’t born knowing how to do new things at an expert level. From babyhood on, most skills humans acquire must be studied and practiced over time.

Pick out a few common skills listed below and have students share thoughts on when, why, and how people learn to do them. Help ensure that examples of repetition and imitation come up in relation to how people learn.

- crawling, walking, skipping, jumping

- talking, whispering, shouting, singing

- reading, writing, following instructions, telling jokes

- making friends, keeping friends

Pilot practice

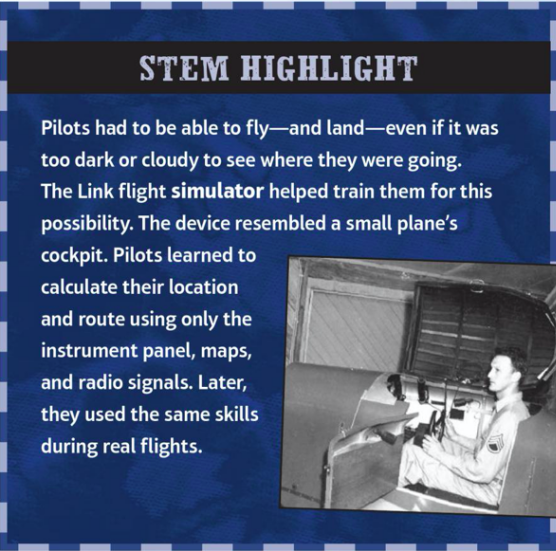

Revisit Chapter 2: “Pilot Training,” and reread the STEM Highlight sidebar.

STEM Highlight passage quoted from page 17: Pilots had to be able to fly—and land—even if it was too dark or cloudy to see what they were doing. The Link flight simulator helped train them for this possibility. The device resembled a small plane’s cockpit. Pilots learned to calculate their plane’s location and route using only the instrument panel, maps, and radio signals. Later, they used the same skills during real flights.

Ask students to consider the benefits of repeated flight simulations, or close imitations (learning with similar controls and processes, safe environment, ability to practice until you’re ready).

See if students can name other activities people practice before doing “the real thing.” Take a few ideas, then lead them through comparing the use of training wheels on a bicycle to using a flight simulator.

Sample questions: What’s unique about riding a bicycle with the training wheels on, and riding the same bike with them off? What are some differences between working with a flight simulator and flying a real plane? How might someone know they’re ready to ride without training wheels, or ready to fly a real plane high up in the air?

Activity: Poetry practice

Read aloud Mother Goose’s classic nursery rhyme “Hickory, Dickory, Dock.”

Hickory, Dickory, Dock

Hickory, dickory, dock,

The mouse ran up the clock;

The clock struck one,

And down he run,

Hickory, dickory, dock.

Invite students to practice writing their own short poem in the style of “Hickory, Dickory, Dock.” The idea is to imitate it using their own words while closely sticking to the rhyme scheme, line-for-line syllable count, and rhythm of the original.

When time’s up, have volunteers share their poems. Ask them to reflect on this “simulation” process. Was it challenging to imitate a specific nursery rhyme? Why or why not?

Next, encourage students to do the same exercise again at home and report back to class on whether the second time mimicking a poem was easier than the first. Then give them the option of gaining additional expertise by writing their own wholly original rhyming poem to share and discuss on a different day.

Featured image: “piano practice” by woodleywonderworks is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Lisa L. Owens has authored more than 100 books for young readers, including early chapter books, graphic novels, middle grade fiction, and a slew of nonfiction for ages PreK–YA. Learn more about her work at llowens.com and @LisaLOwens.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.