GUEST BLOGGER ANITA SANCHEZ

In writing nonfiction, one of the first—and hardest–choices to make is to decide who should tell the story. From whose point of view do you want the reader to see the events that are about to unfold?

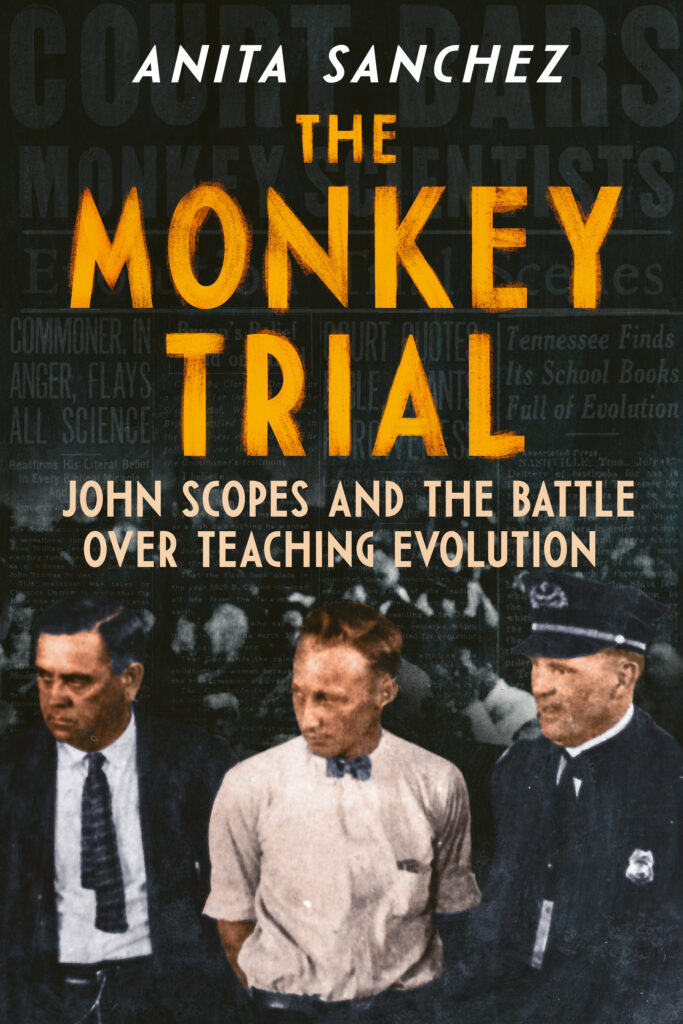

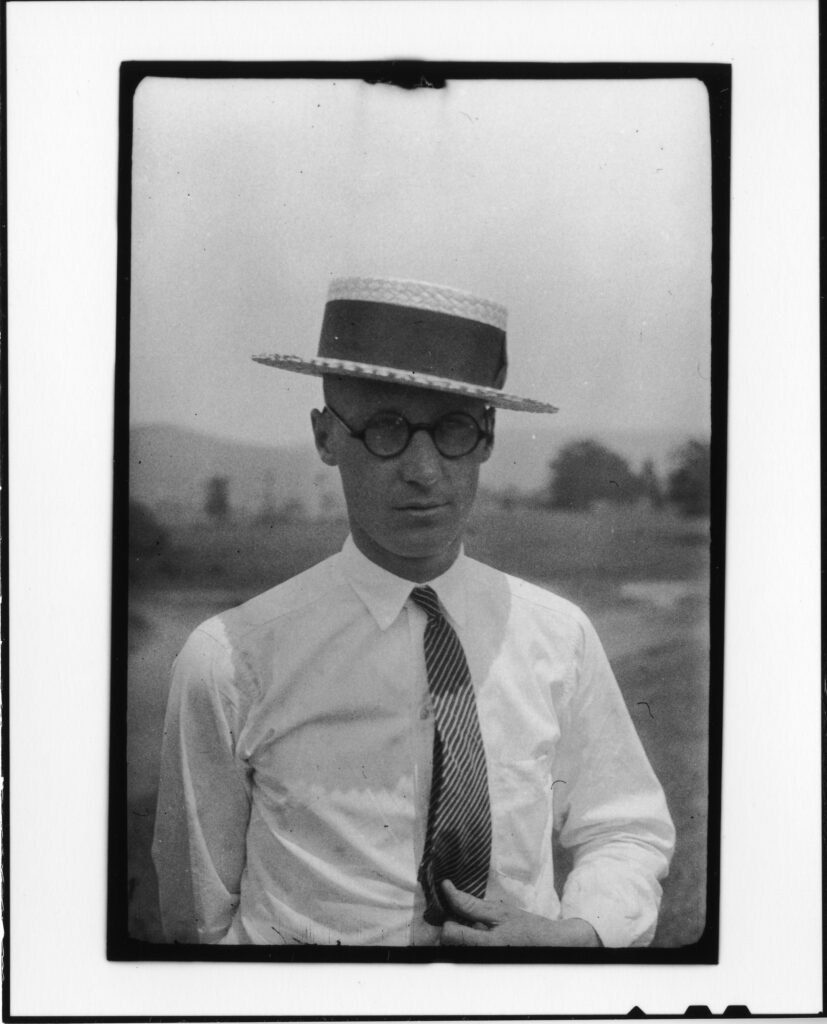

In writing my nonfiction book The Monkey Trial, I had a large cast of characters. There was John Scopes, the teacher who was arrested for teaching evolution. (In 1925, the state of Tennessee passed a law forbidding the teaching of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution in public schools.) There was Clarence Darrow, the famous attorney who defended him. There was William Jennings Bryan, the politician who led the prosecution, and also Howard Morgan, a fourteen-year-old student who testified that Mr. Scopes had taught evolution to his biology class.

What to do…

It was difficult to decide how to tell this complicated story. In a fiction book, you can invent characters and make up their thoughts, actions, and words. But in nonfiction, the author must have each person’s thoughts and actions reflect what really happened. Choosing a point-of-view character is limited by how much you can find out about what the character experienced.

Fortunately for me, the trial was covered by more than two hundred reporters, who collectively wrote more than two million words about the trial and the people in it. Every minute from the opening prayer to the final bang of the judge’s gavel was recorded by the court stenographer. John Scopes wrote a wonderful autobiography that preserves the flavor of the times, right down to the sodas in the local drugstore. This gave me a great deal of information about John’s actions, and more importantly his thoughts and emotions, and he is the main viewpoint character. But to tell such a complex story, I decided to use an omniscient of view, changing from person to person as the story progressed.

Activity: Whose point of view?

Ask the students to choose a short section of the text and read it aloud. Then decide whose point of view that section is told from. Ask them to list the clues that reveal who is the POV character.

A good example might be the Introduction, written from the point of view of Howard Morgan, a high school freshman.

How do we know this section is from his point of view? Because as he walks through the courtroom we only see what he sees and know what he knows. He recognizes Clarence Darrow, describing for us what Darrow looks like. If this section was from Darrow’s POV, the text would describe a boy walking tensely towards the witness chair. Instead we see Darrow as Howard does: a famous lawyer, wearing a pair of bright purple suspenders.

Another good example of point of view is the cross-examination of William Jennings Bryan in Chapter 8. John Scopes took no part in the action—he sat watching, a silent observer. But we see the scene through his eyes. We feel his emotions of triumph when Darrow scores a key point, and pity for Bryan as the older, exhausted man is humiliated.

Activity: What’s going on in their heads?

Ask the students to scan the selected text section to identify cues that help us understand the emotions the point of view character is feeling.

At no point does Howard think to himself, “Boy, I’m really nervous.” But wearing his tie askew under one ear, his hands tightly clasping the arms of the chair, and his muttered answers to the prosecutor’s questions provide clues that he’s scared and nervous.

William Jenning’s Bryan’s sweaty, red face, untidily unbuttoned jacket, and constant fanning of himself with a palmetto fan are all clues that he is physically and emotionally in trouble.

As Atticus Finch says in To Kill a Mockingbird, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view…until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.” So whenever you write a story—fiction or nonfiction—consider carefully which character’s skin the reader should climb into.

As a science writer, Anita Sanchez is especially fascinated by plants and animals that no one loves. Her books get kids excited about science and the wonders of the natural world. Many years of field work and teaching outdoor classes have given her firsthand experience in introducing students to nature. She is the award-winning author of many books on environmental science for children and adults.

- Website: Anitasanchez.com

- Instagram @anitasanchezauthor

- Facebook: Anita Sanchez

- Twitter/X: @asanchezauthor

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.