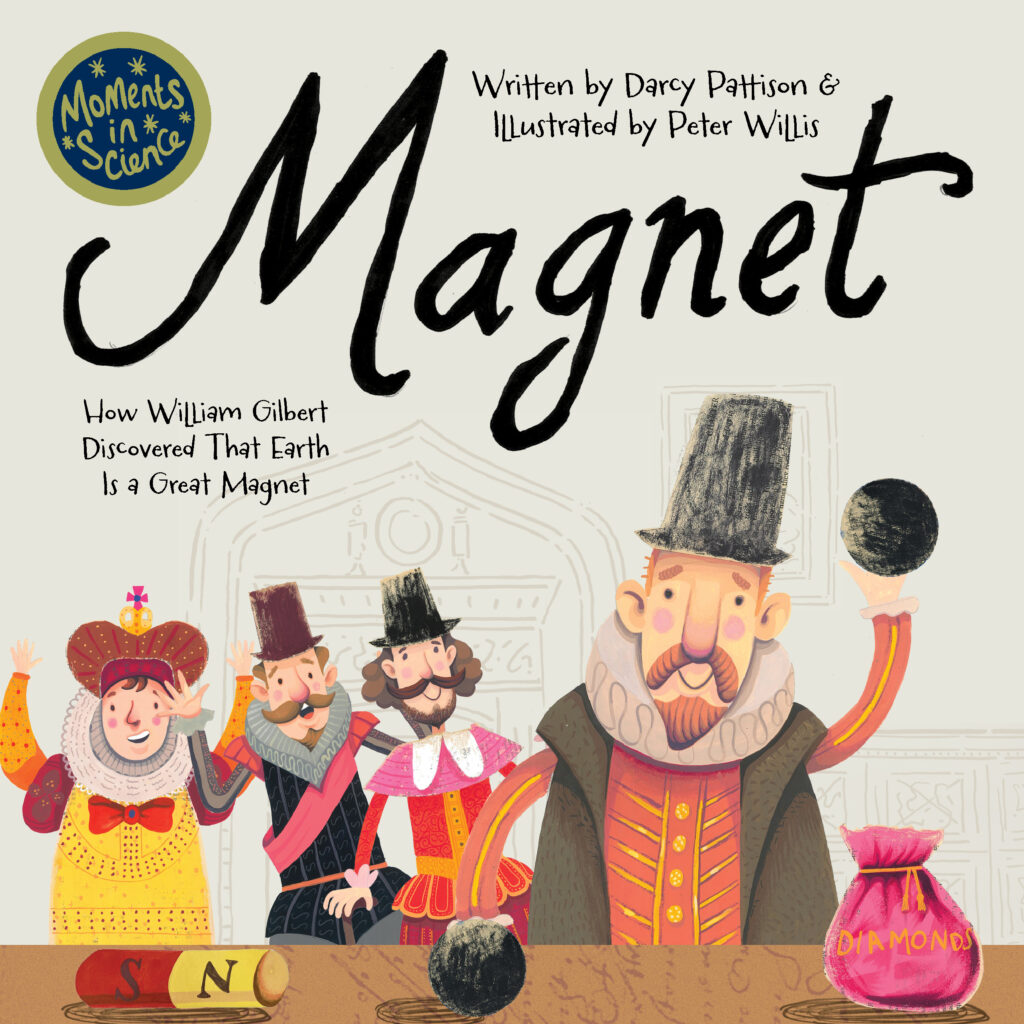

GUEST BLOGGER DARCY PATTISON

The Moments in Science nonfiction book series takes a look at basic ideas in science and a moment when something changed. Usually it’s a moment when our understanding became clearer, or scientific principles are explained in new ways. The latest book in the series, Magnet: How William Gilbert Discovered that Earth is a Great Magnet explores basic magnetism observations that led to a far-reaching observation that Earth itself must be a “great magnet.”

Background

William Gilbert (1544-1603), a court physician to Queen Elizabeth I, experimented with natural magnets called lodestones. He lived at a time when science was changing. Before his time, scientists thought about the world and developed theories about how things worked. But Gilbert did experiments, made observations, and used models to understand medicine, chemistry, astronomy, magnetism, and electricity. He was a modern scientist, not relying on thinking but actual observations.

His magnet experiments are described in this story. There were two basic questions.

- Why does a compass needle (a magnetized piece of metal) always point north?

- Why does a compass needle dip toward the Earth?

Study the basics

Gilbert’s experiments included basic questions because at the time myths confused the study of magnetism. First, he experimented to discover what magnets attracted or didn’t attract. Then, he studied if the results changed when a magnet was in the presence of something like garlic, or if it changed based on time of day. Slowly, the basics of magnetism became clearer.

Scientists usually need to understand the small things before they can answer the big questions. Before Gilbert could understand why a compass needle pointed north, he had to understand the basic ideas about magnets. Only then could he understand that a magnetized bit of iron like a compass needle would only point north if it was aligning with the magnetic fields of Earth itself.

How to repeat William Gilbert’s tests

- Test common items in your classroom to see if they are attracted by a magnet. Make two piles of items, Magnetic or NOT Magnetic.

- Does garlic weaken a magnet? Put the magnet next to a clove of garlic and repeat the tests. Or hold a magnet and garlic clove in the same hand as you test items. Did you move any items from the Magnetic pile to the NOT Magnetic pile, or vice versa?

- Are magnets weaker at night? For homework, test the same or similar items at home. For example, if you test a wooden chair at school, test a similar wooden chair at home. Did the wooden chair change category?

- Testing 75 diamonds. Discuss how many times you need to test an item or similar items before you can make a statement that it is magnetic or not. For example, is it enough to test the magnetism of just one pencil? Or should you try 75 pencils? Repeat the Magnetic/Not Magnetic test with multiple pencils. Think about when it would be important to repeat a test with many items.

Why repeatable results?

Scientists often talk about experiments that are repeatable. The experimental results should be the same regardless of geography, time, or other factors. Gilbert worked over 420 years ago, yet his experiments still give the same results. Write about why it’s important for science experiments to be repeatable.

Featured image credit: “File:A-1 horseshoe-magnet-red-silver-iron-filings-AHD.jpg” by Oguraclutch is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Children’s book author and indie publisher Darcy Pattison has written over seventy award-winning fiction and non-fiction books for children. Five books have received starred PW, Kirkus, or BCCB reviews. Awards include the Irma Black Honor award, five NSTA Outstanding Science Trade Books, four Eureka! Nonfiction Honor book (CA Reading Assn.), two Junior Library Guild selections, two CLA Notable Children’s Book in Language Arts, a Notable Social Studies Trade Book, a Best STEM Book, an Arkansiana Award, and the Susannah DeBlack Arkansas Children’s History Book award. She’s the 2007 recipient of the Arkansas Governor’s Arts Award for Individual Artist for her work in children’s literature. Her books have been translated into ten languages. Find her online.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.