GUEST BLOGGER: CAROLYN DeCRISTOFANO

Metaphors in language arts AND science

I’m so pleased to be able to share some thoughts on linking science trade books such as A Black Hole is NOT a Hole with literacy. Many thanks to Patti for offering this opportunity! I’m especially excited about this post’s topic—metaphors. As an example of figurative speech, metaphor is a topic that shows up often in the ELA Common Core State Standards, as highlighted below. Additionally, adept use of metaphors is strongly connected to developing models, the second in the NGSS list of science and engineering practices.

Metaphors help us make connections

Metaphors add spark to writing and engage us as readers, but they are more than just a powerful writing and communication tool. Thinking metaphorically helps us think, period. Scientists use them as they build and model new knowledge and concepts. (I generally think of thinking and learning as communicating to myself.) As every poet or poetry lover knows, metaphors also help us make associations, some of them in the emotional or subconscious realms. Closely related to metaphors are similes; some sources even classify similes as a special case of a metaphor, a perspective I take for the purposes of this lesson. Similes make comparisons between two objects but use “like” or “as” in expressing the relationship.

As in other genres, it’s important to unpack metaphors in informational text and content learning. Additionally, metaphorical thinking can help lifelong learners make connections between new ideas and old, and between seemingly unconnected concepts. Fostering student growth in these areas expands their avenues to understanding and allows them to avoid misconceptions that might be implied with some metaphors that we all encounter.

Good Metaphor Gone Bad

For example, before I conceived of writing A Black Hole is NOT a Hole, in my author visits for Big Bang: The Tongue-Tickling Tale of a Speck That Became Spectacular, students would spontaneously bring up black holes (presumably because of their connection to the cosmology theme). Many would ask questions about what would happen if a black hole “came and got them,” or similarly attacked. Their eyes wide, they would insist on returning to the question, even after I offered reassurances that black holes are very far from Earth.

Where did students pick up the impression that black holes could pose a danger to them? A quick look at many popular media outlets gave me an answer. Black holes were hungry beasts. Monsters. Predators. Catchy figurative language apparently led younger readers to anxiety and misunderstandings about black holes. While discussing black holes with adults, I soon learned that the idea of a “hole” was misleading, too. In fact, from one such discussion, the idea for the book was born. Metaphorically. In any event, these conversations helped me frame one of my purposes in writing A Black Hole is NOT a Hole. I was going to avoid the “beast” concept at all costs and create new, more explanatory metaphors to help readers wrap their minds around black holes. That means that A Black Hole is NOT a Hole can be a useful text in the ELA as well as the science classroom—but of course, I encourage you to explore metaphor with lots of STEM trade books!

Have you heard the news?

Excerpt from A Black Hole is NOT a Hole by Carolyn Cinami DeCristofano

In outer space, mysterious entities called black holes seem up to no good. From the headlines, you’d think black holes were beasts with endless appetites, lying in wait for the next meal. By some reports they are “runaway,” out-of-control “predators” that “feed” on galaxies, only to “belch” and “spit out” what they don’t eat. They “lurk” in the shadows, “mangling” stars and “gobbling” them up. In short, they have a nasty reputation for being monsters “gone mad.”

Teaching about Metaphors in Science and ELA

I hope the progression of activities below, which is based on one of my author programs, will help you and your students engage in metaphors in satisfying, creative, and thoughtful ways. Also be sure to check out the additional resources at the end of this post.

Part 1: Act Out Metaphors (Introduction/Review)

While you may have your own approach to introducing and exploring metaphors, here’s an engaging option that has worked for me. In this activity, students explore metaphors with an acting/role-playing activity. Depending on the examples you choose, you may want to provide props, such as pictures or stuffed toys, which can help represent nouns or actions that are used metaphorically.

Step 1: Introduce the activity.

Of course, you want to let students know that in this activity you’ll be exploring metaphors and how they work. Preview how the activity will run. Then give it a go!

Step 2: Ask students to act out or portray a specific object (or verb).

For example:

- You can ask them to do their best impersonations of a bee. As an alternative, you can have just one student demonstrate. Choose someone who enjoys the spotlight.

- Students might buzz, flap their arms as if they were wings, “fly” from imaginary flower to imaginary flower.

Step 3: Next, use the name of this object in a sentence metaphorically.

For example:

- “At first, Emma didn’t do much research, but the week before her report was due, she became a busy bee.”

- Ask students to act out the sentence’s literal meaning, enjoying the challenge and silliness of acting out someone literally transforming into a bee.

Step 4: Emphasize the idea of a metaphor as a comparison between two objects or ideas, not to be taken literally.

Acknowledge that the sentence probably should not be taken literally. Lead a discussion of what the sentence really means. For example:

- What might “Emma” and a busy bee have in common? (How does the metaphor fit?)

- How might comparing Emma to a busy bee affect listeners? What if the sentence just said that Emma did a lot of work? What would be the effect of a different metaphor for the same idea? (For example: “Emma was a whirlwind” implies a lot of action, but something that may be less productive or organized than bee activity.)

- What aspects of a bee don’t fit this comparison with Emma?

Step 5: Repeat to help students solidify their understandings.

Instruct students to act out a few more examples. Here are some possibilities; note that not all of them are as easy to act out as the example above, but students can improvise.

Examples:

- When I looked at the kitten my heart melted.

- Ebeneezer was an old crow.

- He was a cold fish.

- My mom is an early bird.

- I was such a slug the other day! I didn’t get anything done!

- The dancers were like snowflakes on a blustery day. [This is an example of a simile.]

- Desperate to avoid her parent’s punishment for sneaking in extra screen time, she reminded them that she had cleaned her room and washed dishes that week. Of course, she knew it was futile, that she was merely grasping at straws.

Before moving on, check for students’ understanding. How well do they seem to grasp that metaphors are comparisons that help us relate one object or idea to another, building off their similarities and ignoring their differences? (The differences contribute to the humor of acting out the literal meaning.)

Part 2: Explore Metaphors in A Black Hole is NOT a Hole

Step 1: Read and make note of metaphors.

First, be sure to read the book—either in small groups, as an extended read-aloud, or as assigned reading.

Ask students to list the metaphors that they notice as they read. They should note any metaphors, not only those referring to black holes. (Introduce and include similes if that makes sense to you. You’ll find more examples if you do!)

You or they should take notes because they’ll refer to this list later. Tracking Down Metaphors in A Black Hole is NOT a Hole is a handout that can help. (Notice that “tracking” metaphor is an example of a metaphor!)

For your reference, examples of metaphors in the book (including similes) include:

- Black holes as predators, beasts, monsters, etc. (Page 1)

- “A black hole is like a giant whirlpool.” (Page 8, caption on Page 11.)

- “Now blazing, flaring, spewing, and spouting, the new star is a fiery furnace.” (Page 20)

- “The plasma rolls and churns like a hyper hurricane of heat, light, sound, and motion.” (Page 21)

- “A black hole is like a hiding place in space, with footprints leading to it.” (Page 33)

- “This nothingness of space was a humongous, rigid background, with all of the matter in the universe arranged on it like pieces on a game board.” (Page 56)

- “(A black hole’s center is) an extremely tiny but extremely heavy object placed on the blanket.” (Page 59)

Step 2: Have students compare notes.

Once students complete their lists, they can compare notes.

In small groups, they can go on to the next step, delving more deeply into a few metaphors, analyzing how each “fits” and “doesn’t fit”, and what impacts it has on them. A second handout, Analyzing Metaphors in A Black Hole is NOT a Hole, can guide students.

Afterward, hold a whole-group discussion about their analyses. Discussion questions might include:

- Which metaphors stood out as especially vivid for students? What made it so striking?

- Metaphors that help explain some new idea work best when the new idea is compared to something familiar, something the reader already knows about through direct experience or prior learning. What examples can students point to of how this worked for them as readers? Were there any comparisons that involved two objects or ideas that were both too unfamiliar to work well?

Part 3: Include Metaphorical Thinking as Part of Science Learning

Now, you’ll engage students in creating metaphors of their own.

Step 1: Begin by helping students identify 1 to 3 target items for the metaphor.

These could be topics they are currently studying in class, or topics (phenomena, objects, etc.) they are exploring or about which they are curious. For example, a student might identify:

- Cell

- Light reflecting off a surface

- Chemical reaction

- Or only one of the above

Step 2: Support students as they create up to three metaphors that can help explain or describe a topic or idea.

They will connect an item/topic with something that is in some important way similar to their topic. A given student can tackle the same science topic three times. For example, the student might choose the topic, cell. He would then identify three different items with which they compare a cell.

Alternatively, a given student might address three different topics–cells, light reflecting off a surface, chemical reaction—and develop one comparison for each.

The handout Make Your Own Metaphor! is inspired by a National Science Teachers Association (now National Science Teaching Association) publication from decades ago that I am sorry I cannot locate and cite. The handout can help students organize their thoughts, but you may need to coach them a bit with questions such as the ones in the table below.

Supporting Students As They Create Metaphors

| General Question | Example |

| What is the topic or item you will explain or describe with a metaphor | A Cell |

| What are some things you know about the item you are trying to explain or describe with a metaphor? | Cells can be ball-shaped; a lot happens inside a cell; a cell makes substances; a cell has chemical reactions; the nucleus of a cell directs all the action; the cell wall keeps some thing in or out of the cell and lets other things through. |

| What do you most want to get across? Is it something about the item’s physical characteristics, or how it functions, how it is constructed, etc? | A lot happens inside a cell, and it’s all coordinated |

| What other, more familiar items share the characteristics that you most want to get across? | A basketball – wait, no, that is a ball, like I imagine a cell, but it’s the shape, not about what happens inside the cell. A basketball team is busy and has coordinated plays A dance A city has all this and also has city hall (the boss, like the nucleus) and has boundaries, too. |

If students are not ready for this leap, you might create a list of possible metaphors and ask students to choose one and develop a rationale for why it would be a good choice for what they want to represent in the metaphor. Include some ideas that really don’t work well, so that students have to be thoughtful.

Step 3: Direct students to share their metaphors with each other and discuss them, using the prompts from Part 2 (analyzing metaphors in A Black Hole is NOT a Hole) as a guide for their analysis and discussion.

CCSS Connections to Figurative Language (Including Metaphor)

Grade 5

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.5.5

Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.5.5.a

Interpret figurative language, including similes and metaphors, in context.

Grade 6

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.6.5

Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.6.5.a

Interpret figures of speech (e.g., personification) in context.

Grade 7

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.7.5

Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.7.5.a

Interpret figures of speech (e.g., literary, biblical, and mythological allusions) in context.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.7.5.b

Use the relationship between particular words (e.g., synonym/antonym, analogy) to better understand each of the words.

Part 4: Taking it Further

Repeating Part 3 whenever possible may be a great way to help students continue to think metaphorically and creatively about their new learning. In addition, encourage them to notice and unpack the metaphors they see in science texts, whether they are reading as part of a classroom, watching science programs online, or seeing current events. Consider assigning them to keep a science metaphor journal; try using Finding Metaphors in Other Science Writing as a log. Frequently revisit the prompts embedded in Part 2’s handout frequently.

Additionally, you might want to informally raise awareness about all of the various metaphors, both explicit and implied, that we use in daily spoken language. Keep a tally of how many metaphors students can notice during normal conversation. You may find it’s rather astounding how many metaphors pepper our language. (P.S. “Pepper” is used as a verb metaphor in the previous sentence. To avoid it, I might have said something about how many metaphors are woven into our language—another metaphor!)

As a final suggestion, you might venture a bit from metaphor and begin exploring analogy. Given that analogies are also a form of comparison, you can adapt the activities and handouts pretty readily. If you are looking for text to study, you can be sure that A Black Hole is NOT a Hole offers plenty of examples of analogy!

Whether you venture beyond metaphor or stay focused on it, I hope that with these activities your students will soon be experts at using metaphors to create bridges between what they know and what they are learning. (Yes: another metaphor–bridges!)

Resources

- Robin Neal’s Metaphor Game includes a simple, engaging approach to teaching metaphor, as well as thoughtful commentary.

- The Art of the Metaphor – Jane Hirshfield is a short video “lesson” on metaphors. This TED Talk publication includes suggestions for exploring metaphors more deeply (and validates some of my suggestions above). While some aspects of this animation might not be a good fit for younger students, other parts, especially the examples of metaphors and commentary help to clarify the concept. It can serve as inspiration for you or as material you can help students unpack.

For your own quick review of metaphors and similes, you might want to see:

- Grammarly Blog article, Metaphors, by Alice E.M. Underwood

- Texas Gateway for Online Resources, by TEA. Imagery: Simile and Metaphor

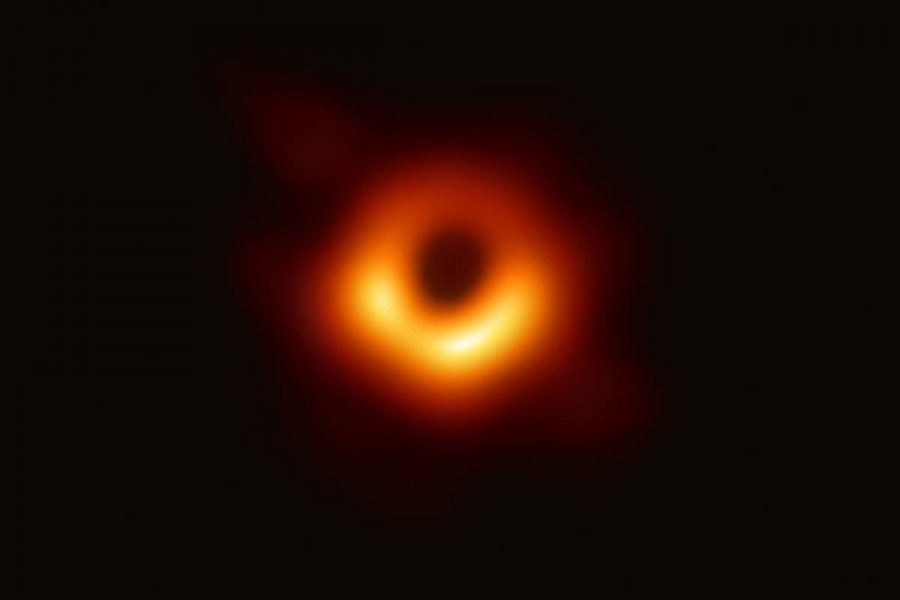

*Featured image: “The black hole at the centre of galaxy M87.” EHT Collaboration from New Scientist

Carolyn Cinami DeCristofano, M.Ed., is a STEM educator and author of several acclaimed STEM books for kids. In addition writing, she consults with two businesses she co-founded: Blue Heron STEM Education, which focuses on curriculum development and teacher professional development, STEM Education Insights, which conducts research and evaluation, and tackles more complex curriculum R&D. She brings enthusiasm, energy, and thoughtful lessons to her interactive school and library programs. For more information, please email her at carolyn[at]carolyndecristofano.com.

2 Comments

Leave your reply.