GUEST BLOGGER SHANA KELLER

The chemistry of bioluminescence is a fairly new subject, one in which scientists and inventors are coming up with new ways to utilize. Whether it’s developing bioluminescent trees that might replace street lamps, or plants that might light up to show farmers when their crops need food or water, the possibilities are endless and cool!

Pre-reading discussion

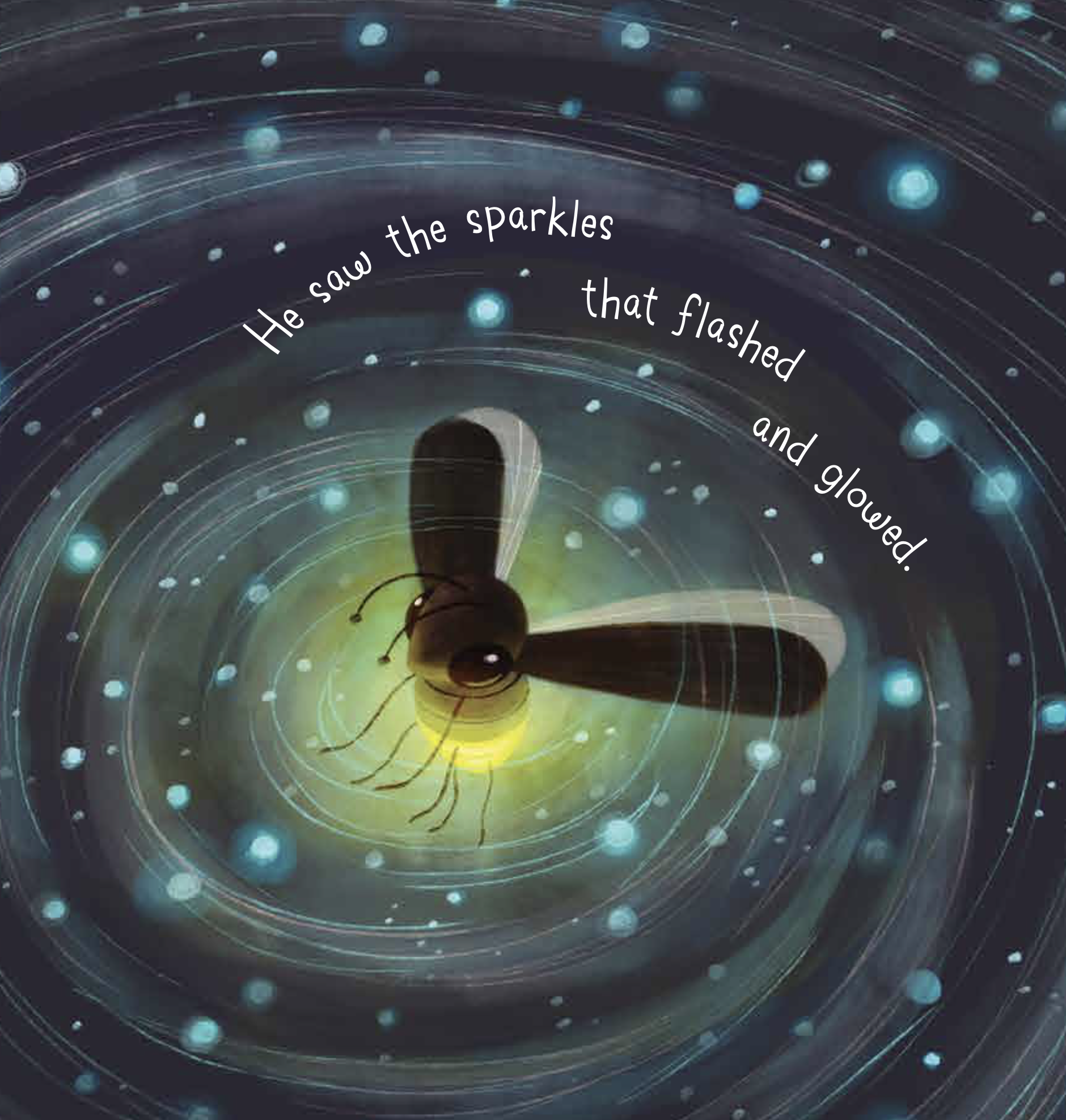

In Fly, Firefly!, scientist Rachel Carson witnesses a firefly trying to dive into an ocean filled with bioluminescent organisms.

Ask your students:

- What do they think bioluminescence is and what purpose it might serve?

- Can they give an example of bioluminescent animals or plants?

Living light

Start the lesson by reading Fly, Firefly! At the end of the story, explore the back matter titled “Living Light.” Discuss the definition of bioluminescence and the difference between fluorescence and phosphorescence.

In the About Rachel section, recap how Rachel and her niece headed down to the seashore off the coast of Maine. On the shore, they turned their flashlights off and saw a sea filled with ocean phosphorescence, most likely a form of marine plankton called Dinoflagellates. Rachel joked how one ‘gem’ took to the air! (It was a firefly who kept diving into the ocean.)

Ask your students:

- Why do they think the firefly was trying to dive into the ocean?

- What do they think caused the flashes in the ocean?

- What would be a benefit or detriment of glowing in the dark?

An easy experiment

In this experiment explore the differences between fluorescence and phosphorescence while creating glowing water.

Materials

- water (plain/tap)

- tonic water

- pliers

- funnel

- 4-6 clear bottles

- measuring cup

- highlighters (multiple colors)

- UV or black light

- tweezers (optional)

- glowsticks

Directions

- Using the funnel, fill 1-4 bottles with approximately 2 cups of tap water, and the remaining bottles with 2 cups of tonic water.

- Use pliers to take the bottom off each highlighter.

- Stick the inside inky pad of the highlighters into a bottle of tap water, and in the tonic water (one highlighter per bottle).

- Reserve one plain bottle of tap water and set aside.

- Let the sticks sit in the water for thirty minutes.

- Remove the insides of the highlighter from each bottle (use tweezers to remove if preferred).

- Turn all the lights out and turn on the UV/black light.

- Remove glowsticks from their package without cracking them.

Discussion

Bioluminescence is often confused with fluorescence and phosphorescence. The difference is that bioluminescence is caused by a chemical reaction. Whereas fluorescence occurs when a short wavelength of light is absorbed by an object and then a longer wavelength of light is emitted. Highlighters are a great example of fluorescence. Phosphorescence is related to fluorescence; however, it does not instantly reemit the light it has absorbed. Glow sticks are a great example of phosphorescent materials.

After the observations are made, have students crack the glow sticks.

Ask your students:

- What are the results?

- Why did the water glow different?

- Why didn’t the plain water glow?

- Why don’t glow sticks glow without being ‘cracked’ or activated?

- What happens when they crack the glow sticks?

Featured image credit: Kobi Studio

Shana Keller is the award-winning author of Bread for Words: a Frederick Douglass Story, an Irma S. Black Honor Award; Ticktock Banneker’s Clock, Best STEM Book, Children’s Book Council; and The Peach Pit Parade, all published by Sleeping Bear Press. Her upcoming picture book Do You Know Them? will be released in 2024 by Atheneum Books for Young Readers. She currently resides in North Carolina. Visit her online at www.shanakeller.com; on Instagram @shanakellerwrites; Twitter @shanakkeller; or Facebook @theshanakeller.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.