GUEST BLOGGER CARMELLA VAN VLEET

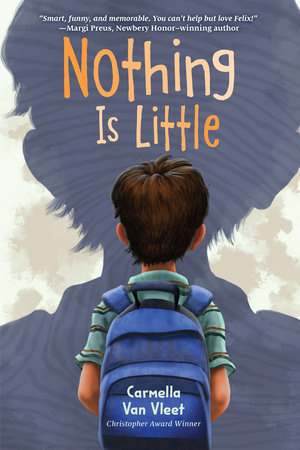

In Nothing Is Little, 11-year-old Felix uses his new-found skills from his school’s Forensic Science Club to help find the dad he’s never met. He also learns about Locard’s Exchange Principle, which says that people bring something to and leave with something from each place they visit. In the end, Felix discovers this applies to the people we encounter in our lives, too.

To solve three set-up crime scenes at school, Felix and the rest of his team utilize several forensic techniques. You can introduce your students to some basic forensic science using readily available items.

Activity #1: Trace evidence

This activity requires a bit of simple advanced planning. Here’s what to do:

- Designate a “crime scene.” For example, your desk and the surrounding area. (No offense. I’m sure your desk is very organized!)

- Trace evidence is small but measurable — little things left at a crime scene. For example: hair strands, fibers, soil, paint chips. After introducing students to the concept of trace evidence, invite them to study your desk for one or two minutes, taking mental notes of what is there.

- During a time when students are not in the classroom, have someone come in to steal an item and “take something, leave something.” (You can also do this yourself.) For instance, while stealing your stapler, maybe the person stepped on the Post-It Note that was on the floor near the desk. And maybe they left a few strands of hair or pebbles from the playground.

- Ask the students to revisit the scene, and see if they can identify the trace evidence and make inferences about the culprit. For example, the suspect could be someone with a Post-It Not stuck to their shoe, have a certain hair color, or been on the playground at some point.

- Then ask students to write up a “police report” that details their investigation.

Activity #2: Finding fingerprints using fumes

Lifting fingerprints from a crime scene can tell investigators who was at the scene. But how can we uncover latent prints that aren’t easily seen on a porous surface? Here’s what to do:

- Have your students gently rub a finger over their nose or forehead. (Having oil on your fingers makes your prints easier to see.) Next, have them press that finger against a unruled, blank notecard.

- Ask students put on safety gloves before pouring 1 tablespoon of liquid iodine and a teaspoon of hydrogen peroxide (both found in the first aid aisle) into a small plastic container with a lid. (Note: iodine will stain skin, surfaces, and clothes, so have students take extra care when using it.)

- Tell students to tape the notecard to the bottom of the plastic lid. It’s important for them to make sure the side with the invisible fingerprint is facing toward the bottom of the container/liquid so the fumes can hit it.

- Have the students seal the lid on the container and wait for ten minutes.

- At the end of the ten minutes, have students carefully remove the lid and card and observe the print.

- Ask them why law enforcement routinely uses fingerprints to identify suspects.

Activity #3: Chromatography

One way investigators might connect a suspect to a crime is by matching the ink of a pen they use. (For example, on a ransom note.) Chromatography is the separation of a mixture into its individual parts or components. Since markers are typically a blend of dyes, we can easily separate them using water if they are the water-soluble kind. Permanent markers won’t work well for this experiment. Here’s what to do:

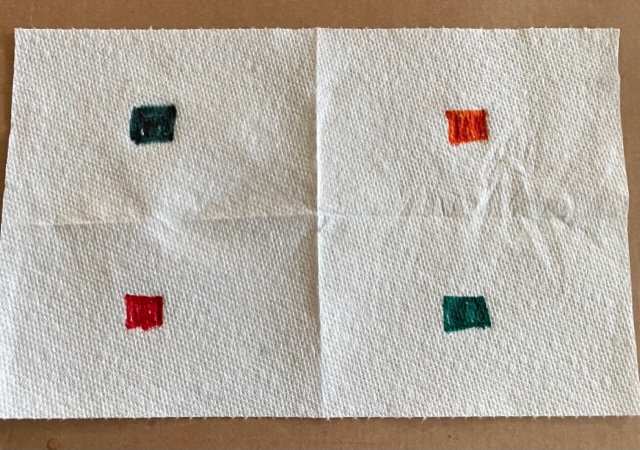

- Have each student lay a paper towel on top of a piece of cardboard or another protective surface.

- Invite students to create four one-inch squares using each of the markers. Tell them to make sure the squares aren’t too close to each other. (In the example, the colors include: black, orange, red, and green.)

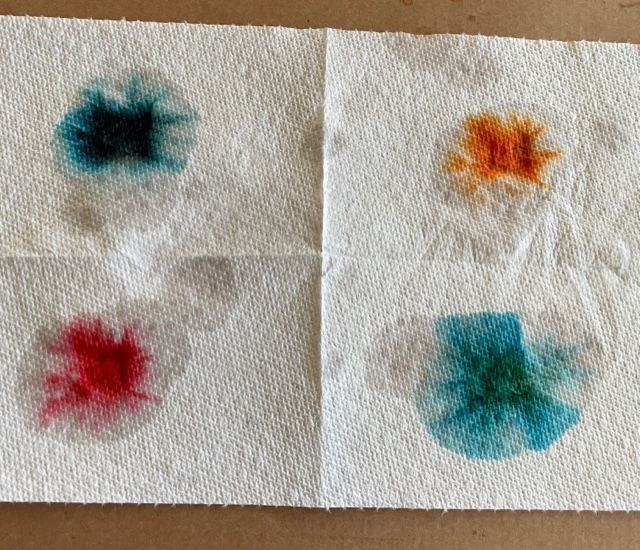

- Have the students use their eye droppers to drop enough water on each square for it to start to spread out. (If you don’t have eye droppers, they can use wet fingers, too.)

- Ask the students to observe and record which colors they see in the ink blots. For instance, a black marker will have shades of blue. Green will have shades of blue.

Featured image credit: “Science Week Launch 2009 Minister Lenihan” by Discover Science & Engineering is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Carmella Van Vleet is a former elementary teacher and the award-winning author of numerous fiction and non-fiction children’s books. Her titles include middle grade novels, Eliza Bing is (Not) A Big, Fat Quitter and its sequel Eliza Bing Is (Not) A Star, as well as the newly released Nothing Is Little (all Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selections). Her pictures books include To The Stars! The First American Woman to Walk in Space, co-authored with Dr. Kathy Sullivan, and the forthcoming You Gotta Meet Mr. Pierce!: The Storied Life of Folk Artist Elijah Pierce, co-authored with Chiquita Mullins Lee. For more information, visit her website (carmellavanvleet.com) or follow her on Twitter (@carvanvleet).

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.