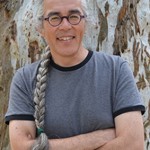

When Christopher Cheng enters a room, the first thing one notices is his long braid. “I haven’t cut my hair in thirteen-plus years,” he says. The second thing one notices is his smile. “I guess I have always been a pretty positive person. I look past the bad and see the good…in people, the environment, in life.” When he begins to speak in his lovely Australian accent, his energy and enthusiasm for life and learning infuse every syllable.

Cheng studied to be a teacher, but there were no classrooms available after graduation. Instead, he began an eight-year career as an educator at the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, Australia. He taught thousands of children about monkeys, pythons, kangaroos, wombats, bats, possums, lizards and more. During his tenure at the zoo, he wrote several brochures, informational articles, and teachers’ guides. Then Scholastic came calling with a book idea. Throughout college Cheng’s children’s literature professor encouraged him to share his stories and he still has copies of his books from childhood, so writing for children seemed like a natural fit. “It wasn’t until my first book came out, Eyespy Book of Night Creatures, that I realized that writing for kids was so very way cool!”

One book became four books, and Cheng was hooked. His life, the environment, the zoo, and the children he met there became fodder for stories. The genesis for One Childbegan during a conversation with some students while Cheng worked at the zoo. They questioned whether one person could make a difference in the world. Cheng’s positive outlook on life would not allow him to believe otherwise, and he set out to prove his case in his book.

Cheng loves museums, and like many authors, finds inspiration in them. In association with Powerhouse Museum, Cheng wrote Australia’s Greatest Inventions and Innovations.Everyone knows that Vegemite (a dark brown spread made with yeast and vegetable extracts, with added spices and minerals) is an Aussie invention, but Cheng wanted to showcase the stories behind other Aussie feats, such as Wi-Fi, dual flush toilets, a blood glucose monitor, and spray on skin for burn victims.

The initial idea for Sounds Spooky came from strange sounds on Cheng’s roof. “We gets lots of sounds on our tin roof, but these were really, really strange,” he says. He scribbled down several ideas for the sounds, playing with words and onomatopoeia. But for anyone who believes that writing a picture book is easy because it’s short, Sounds Spooky contradicts that theory. It took Cheng ten years to perfect the suspense, the rhythm, and the scary mood of the story.

Research is a huge part of Cheng’s writing process. While writing New Gold Mountainand The Melting Pot, two historical fiction titles, Cheng says, “I spent ginormous amounts of time researching…I spent three months buried in our oldest library and in the national archives uncovering letters and documents and reference material to add to my accumulated knowledge. I read stacks of newspapers of the day (1860s) and copied heaps, and then spent the next three months writing and rewriting and rewriting and rewriting the manuscript.” One of the many thrills Cheng experienced while working on these projects was the librarians’ enthusiasm at unearthing a new source or suggesting a new research tactic.

Sometimes, however, Cheng’s research takes a more practical turn. Python is his lyrical ode to a fascinating creature, and the Taronga Zoo was his library. “Living with the wonderfully glorious slithery animal for [almost] eight years taught me nearly all that I needed to know,” Cheng says. “I just love the massage that an adult diamond python gives while slithering across the shoulders!”

Cheng welcomes editorial feedback on his work. “I cannot do without my editors. I need my editors. I adore my editors,” he says. “That said, I have been more stubborn as I have progressed. Where I once always said ‘yes’ [to changes], I now say, ‘let’s think about that.’ Then we to and fro. Sometimes I stick to my guns, other times I agree with their suggestions.”

The morning hours are Cheng’s creative time, and he takes full advantage of a quiet house after his wife, also a teacher, leaves for work. “I kick my wife off to school, answer emails, and then I write for the morning disturbed only by a freshly brewed pot of tea (read here, no teabags).” Cheng takes great pride in making his own lunch—no fast food–unless it is a “boys’ lunch day” in which case, he meets his neighbor at a local café. Although he may edit a manuscript later in the day, he says “my gray cells are stuffed and my synapses are totally not firing by the afternoon.” When his wife returns home from school, they catch up over afternoon tea.

Cheng sums up writing in one sentence, “I have the best job in the world!” He masterfully communicates this enthusiasm in every book.