BY PATRICIA NEWMAN

Do you have one of those students in your classroom who will read anything as long as it’s about sharks? Sharks are a favorite topic for many kids in school, and this science experiment is sure to fire them up.

In preparation

Read Sharks Unhooked: The Adventures of Cristina Zenato, Underwater Ranger. This dramatic story and Cristina’s courage will capture kids’ imaginations. As you read, ask your students to be aware of the shark behaviors in the book. Here are some discussion points to get you started:

- Describe the habitat of the Caribbean reef sharks in the Bahamas.

- Cristina loved sharks as a girl, yet she’d never seen one. Why do you suppose she loved them?

- Can you name some of the things sharks are particularly good at? (possible replies include sense of smell, strength and speed, dermal denticles that help them swim silently)

- Why are sharks such good swimmers?

- What role do sharks play in the ocean?

- Describe how Cristina might have built trust with the sharks?

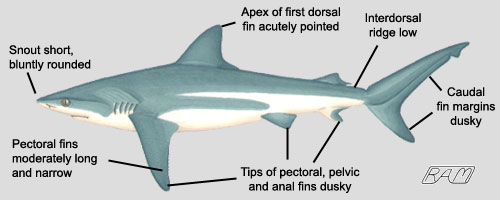

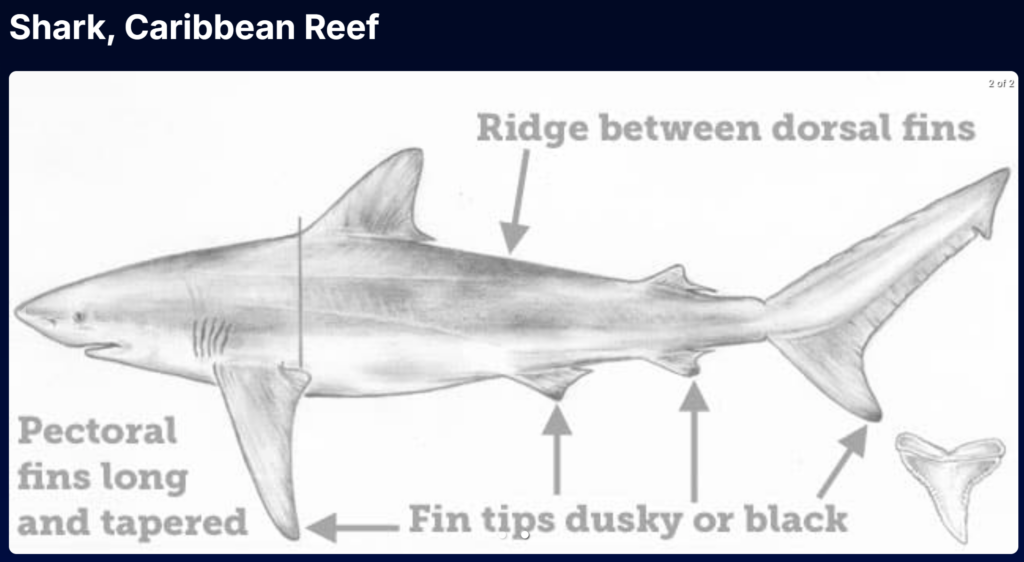

Making model sharks

Provide a variety of art materials (paper, colored pencils, clay, pipe cleaners, etc.) and ask students to build a model of a shark. Ask students to labels the parts of their shark (NGSS, Science and Engineering Practices 2, Developing and Using Models). Here are two possible sources to get you started.

Science experiment: Why don’t sharks sink?*

We’ve already established that sharks are excellent swimmers. They swim long distances with speed. Their dermal denticles (teeth-like scales) enable silent swimming for more efficient hunting. But one thing we haven’t discussed is how they hover in the water so effortlessly. Any diver knows how challenging it is hover in the water without having to move your arms and legs. They must adjust their air in their vests to achieve neutral buoyancy.

Begin the science experiment by asking students, Have you ever tried to float in water? How did you do it? Chances are they have to make a lot of little adjustments to remain in place, without floating to the top or sinking to the bottom.

Now ask, What is a shark’s skeleton is made of? I’m betting at least one of your students will know that sharks have skeletons made of cartilage rather than bones. Cartilage is lighter than water, which helps sharks remain neutrally buoyant. That’s one part of the answer.

A large, oily liver is the other part of the answer. Conduct the following experiment with your students to demonstrate how oil in the liver helps sharks remain neutrally buoyant.

You’ll need the following materials

- Two or three clean large bins about 2/3 full of water placed in different locations in the classroom

- A small plastic water bottle for each student in the class, half of them empty

- Sharpies of different colors, thicknesses

- Cooking oil

- Science notebooks, pencils

Divide students into groups of two. One child receives a full water bottle; the other child receives an empty water bottle. Ask students to decorate their bottles like a shark. Ask children with empty water bottles to fill them with cooking oil.

Prediction

Tell students they will put their bottles in a bin of water and record their results. Ask them to record in their science notebooks a prediction of what will happen.

Experiment

Next, ask students to choose one of the water bins around the room and test their bottles. Ask them to record the results in their science notebooks.

Discuss each group’s results as a class. Did any group have different results? Ask students to explain their results. Why did the bottle filled with oil float?

*With thanks to Ulster Wildlife’s Sea Deep for this lesson.

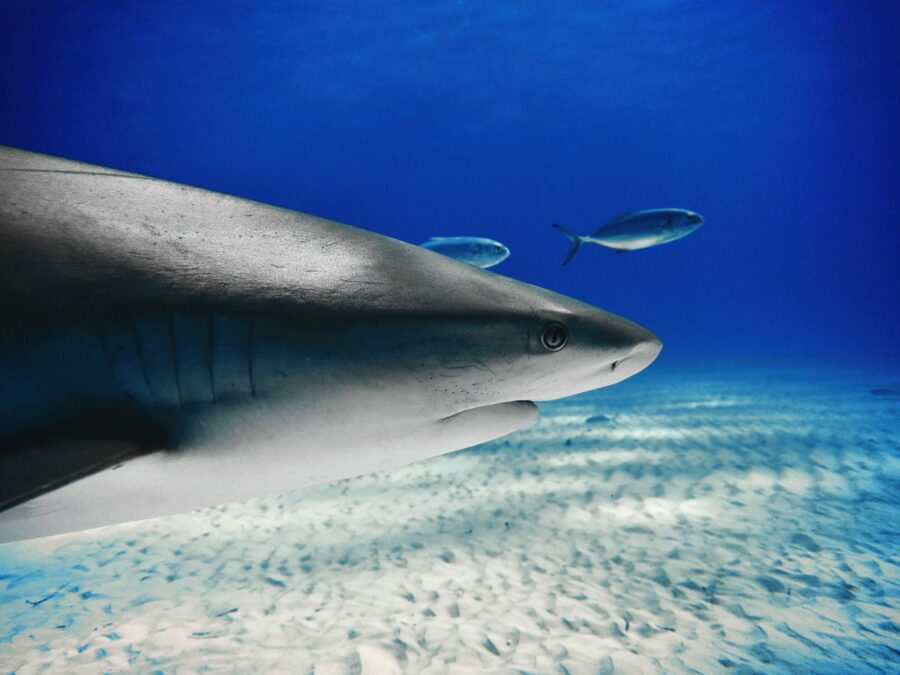

Featured image credit: “Head close-up of a Caribbean Reef Shark at Tiger Beach, Bahamas” by Dennis Hipp (Zepto) is marked with CC0 1.0.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.