GUEST BLOGGER MARISSA MOSS

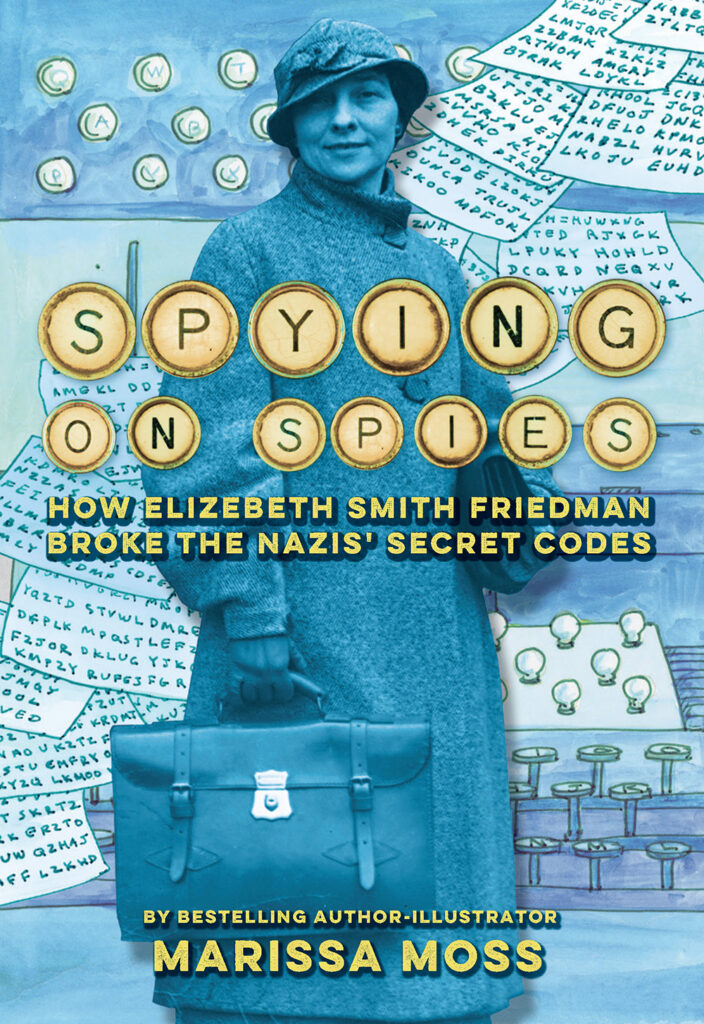

Elizebeth Smith Friedman was one of America’s first codebreakers. She cracked codes for the US government during WWI, throughout Prohibition when gangsters caused a lot of violent crime, and during WWII.

During Prohibition, as part of the Treasury Department, Elizebeth solved intercepted coded messages from criminal gangs. She was so successful, her work led to hundreds of high-profile prosecutions, including the notorious brother of Al Capone. Working for the Navy during WWII, her small unit cracked the Enigma machines used by the Nazis among a vast network of spies in South America. Alan Turing at the famous Bletchley Park did much the same work, but he had the help of a staff of thousands and an early proto-computer, the Bombe, while Elizebeth did all her solving with pencil, paper, and brain power.

This is STEM power at its most compelling and adventurous!

Different kinds of codes

Introduce students to the following types of codes. Then ask them to choose their favorite and write a coded message for a classmate to decode.

Ladder codes

Here’s an example of a ladder code. Ask students to figure it out by looking at the text.

I S N E O D A U L O I K S E U T T

H I S A C E C S T O L E N N B I O

T S A K Y B E E I K S N O S E S N

This is called a ladder code because that’s how you read it. If you read the letters in the normal way, left to right, top row to bottom row, it looks like nonsense. What if you start from bottom left-side to top and back down again, like going up and down a ladder? What does this sentence say?

Grid codes

A grid code is like a ladder code because it also depends on how the letters are arranged. This looks like nonsense:

T W R D H O O S E R S A

P D E Y A I B I S S U T

But what if you knew that you need to re-arrange these letters into a 6-letter by 4-letter grid? Then you would have:

T H E P A S

W O R D I S

R O S E B U

D S A Y I T

Ask students to tell what the message says by reading it left to right, top to bottom? Makes sure they understand that the code above came from taking these letters and rearranging them to go from top to bottom, left to right.

Key codes

Here is a typical code used in WWI. It’s a key code, meaning you need to have the key to read any messages in it. The key is created by lining up five letters on top, the same five on the side and filling in the alphabet inside the grid. Since there are twenty-six letters in the alphabet, not twenty-five, the letter “y” is left out. If you need it for your message, you can use “i” instead.

B L Q W J

B| K A Z N W

L| F J Q R E

Q| B P U T M

W| H S X C G

J | I L O V D

To encode, you use pairs of letters, one from the side of the grid, one from the top to get to the letter you want. So BB = K, BL=A, BQ =N, etc. Knowing that, ask students to decode the following message:

QW WB LJ WW JQ BW QW BL WW QW JB WL LL JQ BW

An extra twist on key codes

To make things really confusing, you can divide the letters up into groups of five (the groups of two are a clue to use key-grid code). Then you would have: QWWBL JWWJQ BWQWB LWWQW JBWLL LJQ BW. This message evenly divides into five-letter groups, but if it didn’t, you could add Ys as your null letters since there are no Ys in the grid.

Elizebeth and codes

Elizebeth started by looking for patterns, trying to be clearly objective about what was in front of her. She saw early on that a big mistake a codebreaker could make was looking only for what they wanted to find. For her, the truth was what mattered most and she spent her life looking for it. On the way, she tracked down some interesting spies, like “the Doll Lady” who was sending information to contacts in Japan during WWII and Oskar Hellmuth, a minor diplomat who was trying to get weapons from Germany to start a fascist take-over of all of South America.

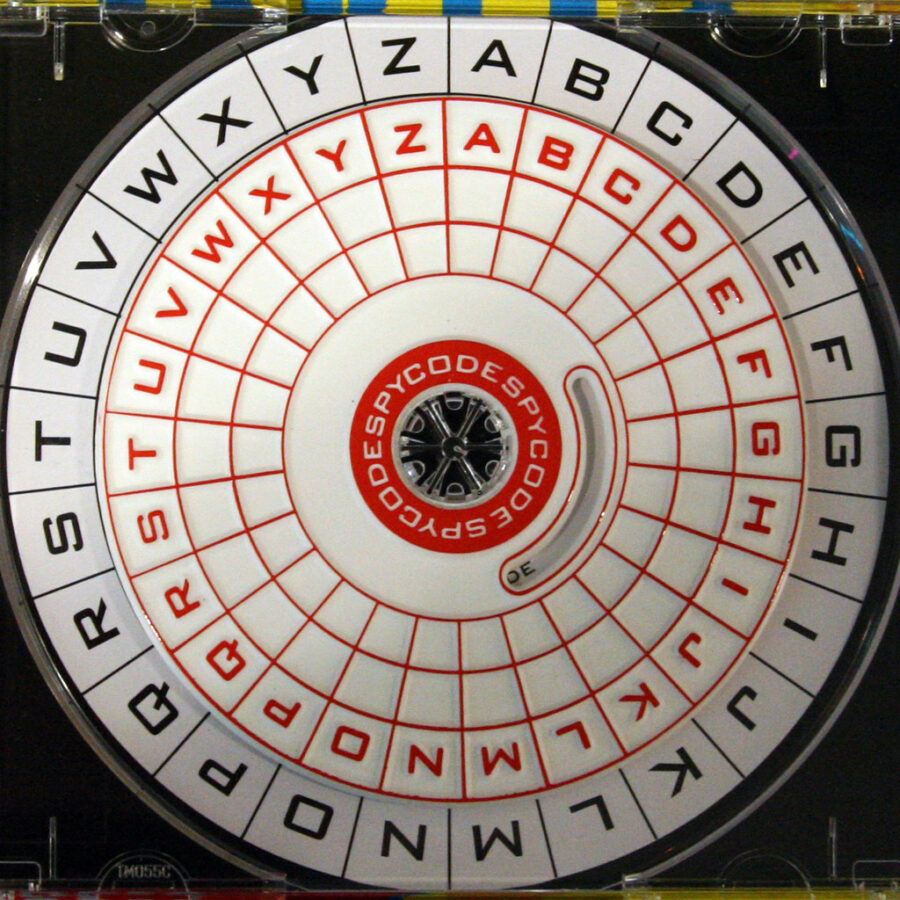

Feature image credit: “code breaker” by Leo Reynolds is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Marissa Moss has written more than seventy children’s books, from picture books to middle-grade and young adult historical novels. She’s best known for the Amelia’s Notebook series, which has sold 6 million copies, been translated into several languages, and started the notebook format craze in children’s books. Her most recent book, The Woman Who Split the Atom: the Life of Lis e Meitner was a Sydney Taylor Notable Book, a Texas Topaz Nonfiction pick, and received several starred reviews. Visit her website or follow her on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.