GUEST BLOGGER HEATHER L. MONTGOMERY

Most students don’t realize that when they have a pencil in their hand, they have choices. Those choices give them a superpower. And with that superpower, they can change the world. But, just as we can’t see a person’s skeleton with the naked eye, most students can’t see the power of their word choices.

In his book, The Art of X-Ray Reading, Roy Peter Clark encourages writers to read as if they are wearing x-ray goggles—reading to discover the hidden tricks behind writing they admire. Let’s help students laser in on word choice and rhetorical devices so that they, too, can wield the right word!

Spotting the tricks together

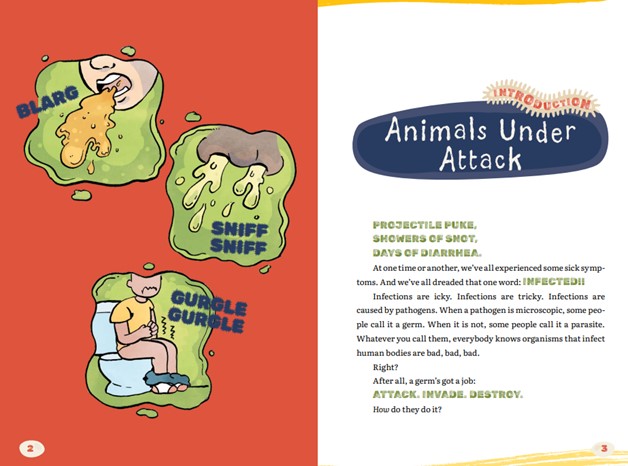

Display this text:

“Projectile puke, showers of snot, days of diarrhea. At one time or another, we’ve all experienced some sick symptoms. And we’ve all dreaded that one word: INFECTED!

Infections are icky. Infections are tricky. Infections are caused by pathogens. When an infection is microscopic, some people call it a germ. When it is not, some people call it a parasite. Whatever you call them, everybody knows organisms that infect human bodies are bad, bad, bad.

Right?”

Sick! The Twists and Turns Behind Animal Germs, Page 3

Read the passage aloud to the class. Ask them what they thought of it. Before re-reading, instruct them to notice words or phrases that led to their personal reaction. After reading, model a response such as, “The word ‘puke’ and the phrase ‘showers of snot’ made me feel grossed out.” Or “When I read ‘icky’ and then ‘tricky,’ I smiled.”

On the board, list words or phrases they cite. Discuss that it may seem like a writer jots down some words and they magically come out as engaging/funny/poetic/etc, but writers practice to hone their skills. This is true of scientific writing as well.

Share this: Just as a doctor (or Minecraft player) uses x-ray to see the hidden, today they will learn to see hidden writing tricks.

Goggles on!

Ask them to read the passage to notice patterns, strategies, or tricks the writer used. Highlight those on the board, providing vocabulary as needed (alliteration, rhyme, repetition, etc.).

Explain that “rhetorical devices” are intentional use of language for a specific effect. Challenge students to find examples repetition in this passage.

If desired, extend the learning by pointing out that the “Infections are icky” passage makes use of repetition in a very special way—at the beginning of multiple sentences—which is called anaphora. Ask them to consider the impact that had on them as they read.

Applying the knowledge

Provide the students with an additional passage. First instruct them to read for pleasure. Then to put on their x-ray goggles and find words, phrases, or rhetorical devices that may have been carefully chosen to bring about an effect.

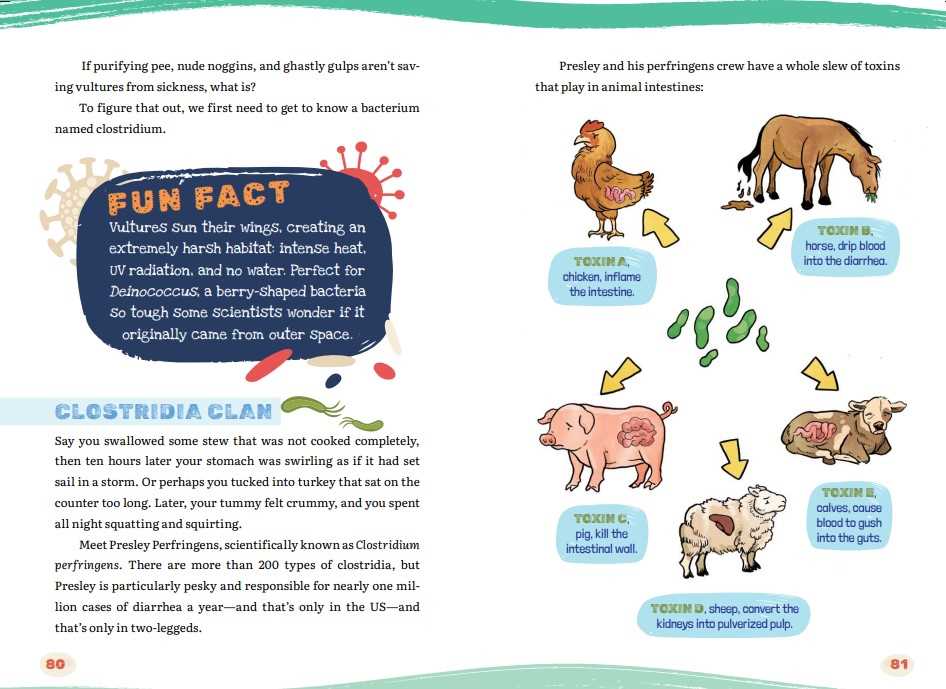

“Clostridia Clan

Say you swallowed some stew that was not cooked completely, then ten hours later your stomach was swirling as if it had set sail in a storm. Or perhaps you tucked into turkey that sat on the counter too long. Later, your tummy felt crummy, and you spent all night squatting and squirting.

Meet Presely Perfringens, scientifically known as Clostridium perfringens. There are more than 200 types of clostridia, but Presley is particularly pesky and responsible for nearly one million cases of diarrhea a year—and that’s only in the US—and that’s only in the two-leggeds.”

Sick! The Twists and Turns Behind Animal Germs, Page 80

Allow students to share their findings. Explain that writing tricks may have different effects on different readers. Ask them to share their favorite.

Now consider how writers use different styles. Have students pair-share ideas about how this information might be presented in a textbook. Challenge them to consider why. Using their textbook as a model, have students re-write the passage. Follow this with a discussion of word choices in scientific writing, lab reports, text for a science fair project, etc.

All of this playing with words can invite STEM-minded kids to enjoy language. All of this science-y writing can invite creatively-minded kids to see the craft in scientific writing. And all of this spying on words can lead to new writing superpowers!

Featured image: “Caught Reading” by John-Morgan is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Heather L. Montgomery writes for kids who are wild about animals. An award-winning author and educator, Heather uses yuck appeal to engage young minds. She has published 18 nonfiction books, including: Something Rotten: A Fresh Look at Roadkill, What’s in Your Pocket? Collecting Nature’s Treasures, and Sick! The Twists and Turns Behind Animal Germs. www.HeatherLMontgomery.com @HeatherLMont

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with me.